Multi-Batch Orders and Cumulative Lead Time: Why Splitting Orders Often Extends Total Delivery Time

When procurement teams face large orders for custom tech gifts—1,200 wireless chargers for a multi-site rollout, 800 power banks for a quarterly employee recognition program, or 600 USB drives for a series of client events—they often decide to split the order into smaller batches to manage risk. The reasoning appears sound: by dividing a single 1,200-unit order into three 400-unit batches, the procurement team can test the first batch for quality, adjust specifications if needed, and avoid committing to the full volume upfront. Suppliers typically accommodate this request, quoting the same per-unit price and lead time for each batch. The procurement team, expecting the total timeline to mirror the lead time of a single batch, schedules the batches to arrive sequentially over three months. In practice, this is often where [production timeline decisions for custom electronics](https://ethergiftpro.uk/news/what-is-minimum-order-quantity-custom-tech-gifts-uk) start to be misjudged. Each batch does not simply repeat the previous batch's timeline; it requires its own setup, sampling, approval, and production cycle, creating cumulative delays that extend the total delivery time far beyond what a single consolidated order would have required. The result is that the procurement team, believing they are managing risk through batch splitting, inadvertently introduces timeline fragmentation that delays the entire project and increases the likelihood of missing critical deadlines.

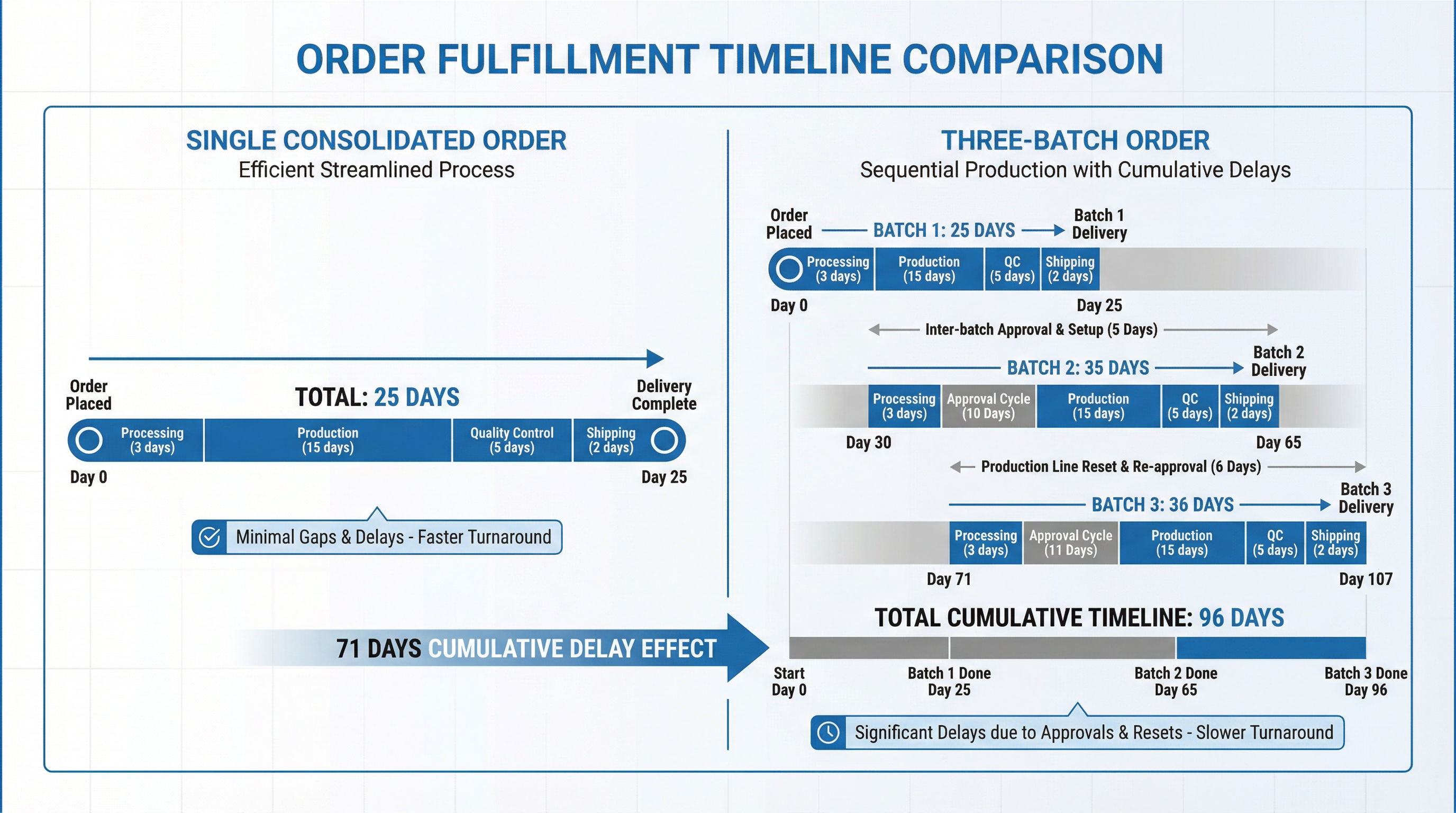

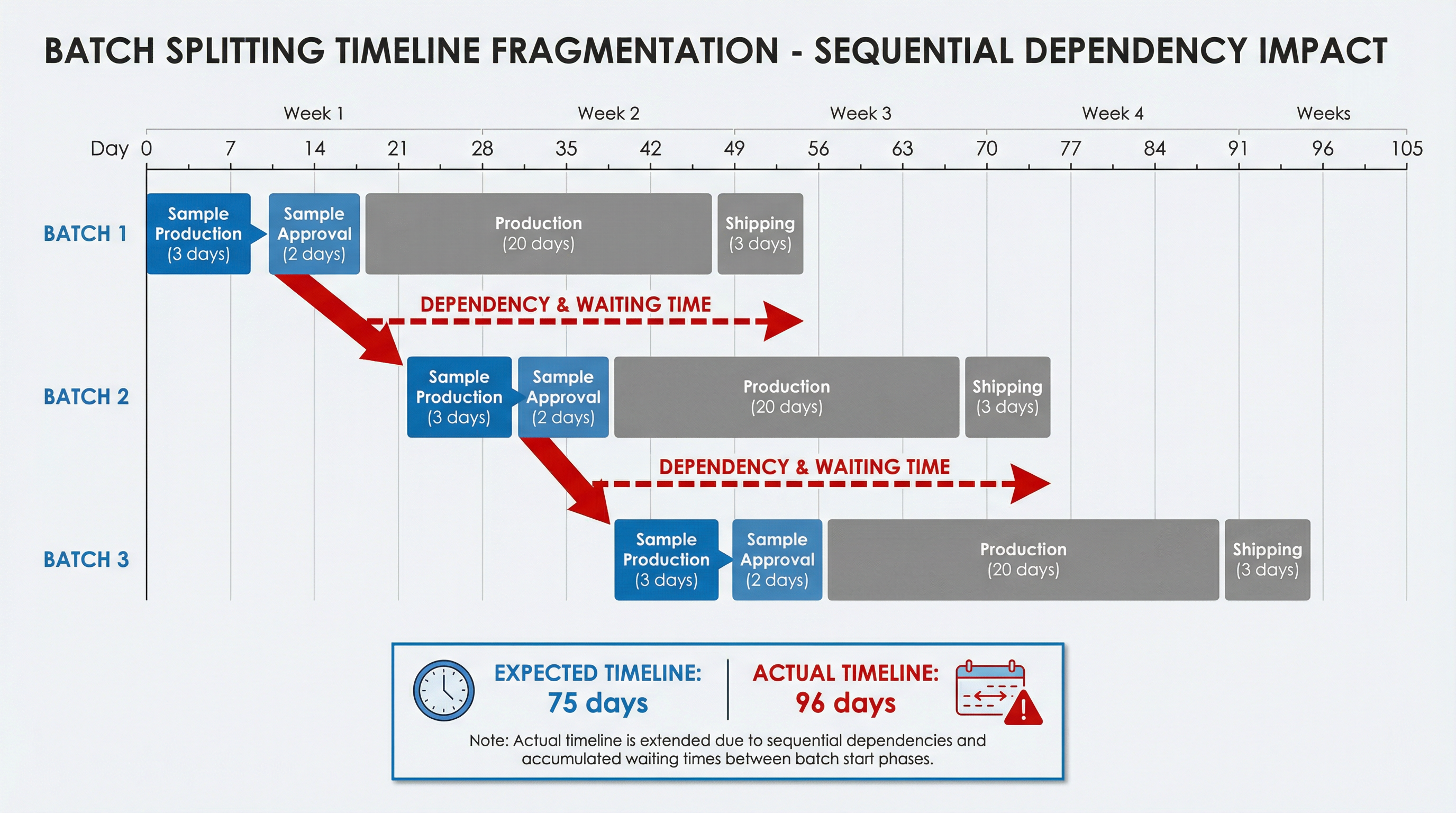

The core misunderstanding stems from treating each batch as an independent, self-contained order when, in reality, each batch depends on the completion and approval of the previous batch. When a supplier quotes a 25-day lead time for a 400-unit batch, they are assuming that the design is finalized, the sample is approved, and production can begin immediately. For the first batch, this assumption holds: the procurement team provides the artwork, the supplier produces a sample, the buyer approves it, and production begins. The 25-day lead time runs from the date of sample approval to the date of shipment. For the second batch, however, the supplier must wait for the first batch to be delivered, inspected, and approved by the buyer before beginning production. If the buyer discovers a minor issue—say, the logo placement is 2mm off-center—they request a design adjustment for the second batch. The supplier must produce a new sample, send it for approval, and wait for the buyer's confirmation before starting production. This adds 7–10 days to the second batch's timeline, pushing the lead time from 25 days to 32–35 days. For the third batch, the same cycle repeats: the supplier waits for the second batch to be approved, incorporates any feedback, produces a new sample if needed, and waits for approval before beginning production. Each batch introduces a new approval cycle, and each approval cycle adds 5–10 days to the total timeline. The procurement team, expecting three batches to take 75 days (25 days × 3), discovers that the actual timeline is 90–100 days due to the cumulative effect of inter-batch dependencies.

A common scenario illustrates this dynamic. A procurement manager sources 1,200 custom-branded wireless chargers for a company-wide employee recognition program. The program runs quarterly, with 400 chargers distributed each quarter. The supplier quotes a 25-day lead time per batch and confirms that the per-unit price remains the same for all three batches. The procurement manager places the first order on January 5, expecting delivery by February 5. The supplier produces a sample on January 10, the buyer approves it on January 12, and production begins on January 13. The first batch ships on February 7, two days later than expected due to a minor production delay. The procurement manager receives the batch on February 10, inspects it, and discovers that the USB-C port is slightly loose on 5% of the units. The manager requests that the supplier tighten the port assembly for the second batch. The supplier acknowledges the request on February 12 and produces a revised sample with the tighter assembly on February 15. The buyer approves the sample on February 17, and production for the second batch begins on February 18. The second batch ships on March 15, 36 days after the first batch shipped—not the 25 days the procurement manager expected. The third batch follows the same pattern: the supplier waits for the second batch to be approved, produces a sample if any changes are requested, and begins production only after receiving approval. The third batch ships on April 20, 36 days after the second batch. The total timeline from the first order to the final delivery is 105 days—40% longer than the 75 days the procurement manager originally calculated. The supplier was not dishonest; each batch did take approximately 25 days of production time. The procurement manager, however, failed to account for the inter-batch approval cycles and the time required to incorporate feedback between batches.

This misjudgment is compounded by the failure to distinguish between parallel and sequential batch processing. Procurement teams often assume that splitting an order into batches allows for parallel processing: while the first batch is in production, the second batch can be prepared, and the third batch can be queued. In reality, most suppliers process batches sequentially, not in parallel, because each batch depends on the feedback and approval from the previous batch. A supplier who receives an order for three 400-unit batches does not begin preparing all three batches simultaneously. They produce the first batch, wait for the buyer to inspect it and provide feedback, incorporate any requested changes into the second batch, produce a sample for approval, and only then begin production on the second batch. This sequential processing is necessary because the buyer's feedback on the first batch often reveals issues that need to be corrected in subsequent batches: logo placement, color matching, assembly quality, packaging design, or labeling accuracy. If the supplier were to produce all three batches in parallel, any issue discovered in the first batch would require rework or scrapping of the second and third batches, resulting in significant waste and delay. Sequential processing protects both the supplier and the buyer from this risk, but it also means that the total timeline for three batches is not 25 days (the time to produce one batch) but rather 75–100 days (the time to produce three batches sequentially, including inter-batch approval cycles).

Another layer of complexity arises from the production line reset required for each batch. When a supplier completes the first batch of 400 wireless chargers, they do not simply leave the production line configured for the next batch. They clear the line, recalibrate equipment, and prepare for the next scheduled order—which may be for a different customer or a different product. When the second batch is ready to begin production, the supplier must reset the line again: load the correct components, adjust the assembly jigs, calibrate the testing equipment, and train the operators on any design changes requested by the buyer. This reset process takes 1–3 days per batch, depending on the complexity of the product and the extent of the design changes. For a three-batch order, the cumulative reset time is 3–9 days, which is added to the total timeline but is not reflected in the per-batch lead time quote. Procurement teams who assume that the second and third batches will begin production immediately after the previous batch is completed are systematically underestimating the total timeline by 5–15 days.

The problem is further exacerbated when procurement teams split orders across multiple suppliers to diversify risk. A procurement manager who sources 1,200 power banks might place 400 units with Supplier A, 400 units with Supplier B, and 400 units with Supplier C, expecting that if one supplier fails to deliver on time, the other two will provide partial coverage. In practice, this strategy introduces additional coordination overhead and timeline fragmentation. Each supplier requires its own sample approval, design confirmation, and quality inspection. If Supplier A delivers first and the buyer discovers a design issue, the buyer must communicate the issue to Suppliers B and C, request design revisions, approve new samples, and wait for the revised batches to be produced. This coordination overhead adds 10–15 days to the total timeline for each supplier, pushing the total delivery time from 75 days (for a single consolidated order) to 100–120 days (for three split orders across three suppliers). The procurement team, believing they are managing risk through supplier diversification, inadvertently introduces timeline complexity that delays the entire project and increases the likelihood of missing critical deadlines.

A more effective approach to managing multi-batch orders is to consolidate the initial order into a single batch, complete the full sample approval and quality inspection cycle, and only then split subsequent orders into smaller batches if needed. A procurement manager who sources 1,200 wireless chargers might place an initial order for 600 units, complete the full production and inspection cycle, and then place two follow-up orders for 300 units each once the initial batch has been approved. This approach ensures that the design is fully validated before committing to smaller batches, reducing the likelihood of inter-batch design changes and minimizing the cumulative timeline impact. The initial 600-unit batch takes 25 days to produce, the first follow-up batch takes 20 days (because the design is already approved and no sample is needed), and the second follow-up batch takes 20 days for the same reason. The total timeline is 65 days—significantly shorter than the 90–100 days required for three sequential 400-unit batches with inter-batch approval cycles.

Procurement teams who split orders into multiple batches without accounting for inter-batch dependencies, production line resets, and coordination overhead are systematically underestimating the total delivery time by 20–40%. This underestimation is not the result of supplier dishonesty or poor planning; it is the result of treating each batch as an independent order when, in reality, each batch depends on the completion and approval of the previous batch. The cumulative effect of these dependencies is that the total timeline for three batches is not three times the lead time of a single batch, but rather three times the lead time plus the cumulative inter-batch approval cycles, production line resets, and coordination overhead. For procurement teams managing time-sensitive projects—employee recognition programs, client events, or product launches—this timeline underestimation can result in missed deadlines, rushed air freight, and reputational damage. The solution is not to avoid batch splitting entirely, but to account for the cumulative timeline impact when planning multi-batch orders and to consolidate initial orders into larger batches to minimize inter-batch dependencies.

The timeline fragmentation caused by multi-batch orders also creates cash flow and inventory management challenges that procurement teams often overlook. When a procurement manager places a single consolidated order for 1,200 units, the payment terms are typically 30% deposit and 70% upon shipment, with the full order arriving in a single shipment. The procurement team pays the deposit upfront, receives the full order 25 days later, pays the balance, and begins distributing the units according to the planned schedule. The cash outflow is concentrated in two payments, and the inventory arrives in a single batch, simplifying warehouse management and distribution logistics. When the same order is split into three 400-unit batches, the payment structure changes: the procurement team pays a 30% deposit for each batch and a 70% balance upon shipment for each batch, resulting in six separate payments spread over 90–100 days. This payment fragmentation increases administrative overhead, complicates cash flow forecasting, and introduces the risk of currency fluctuation if the supplier invoices in a foreign currency. The inventory also arrives in three separate shipments, requiring three separate receiving inspections, three separate warehouse entries, and three separate distribution cycles. For procurement teams managing multiple projects simultaneously, this administrative and logistical overhead can become a significant hidden cost that offsets any perceived risk reduction from batch splitting.

The strategic implication is that multi-batch orders should be reserved for situations where the risk of design failure or quality issues is genuinely high—such as first-time orders with a new supplier, complex custom designs with multiple components, or products that require regulatory testing and certification. For repeat orders with established suppliers, standard designs, or products with minimal customization, the timeline and administrative overhead of batch splitting typically outweighs the risk reduction benefits. Procurement teams who default to batch splitting as a standard practice, regardless of the specific risk profile of the order, are systematically extending their total delivery timelines and increasing their administrative costs without achieving meaningful risk reduction. The more effective approach is to assess the risk profile of each order individually, consolidate orders where the risk is low, and reserve batch splitting for situations where the risk is genuinely high and the timeline impact is acceptable.